Common Lambsquarters Seed: Identification, Uses & Control

- September 2, 2025

- By Oliver Denver

I’ve been doing some research into common weeds, and one that keeps popping up is lambsquarters. It’s fascinating how this plant, often seen as a nuisance, actually has a long history and multiple uses. From its early days as a food source to its persistent nature in our fields and gardens, understanding lambsquarters seed and the plant itself is key to managing it effectively. I want to share what I’ve learned about identifying it, its surprising benefits, and how to keep it in check.

Key Takeaways

- Common lambsquarters is a widespread annual weed, easily identified by its mealy, whitish coating on the undersides of its leaves and often reddish-streaked stems.

- Each lambsquarters plant can produce over 70,000 seeds, which can remain dormant in the soil for decades, making them persistent.

- Historically, lambsquarters greens and seeds were used as food, offering good nutritional value, and the plant even has some medicinal properties.

- While edible in moderation, lambsquarters can be toxic to livestock in large amounts due to oxalates and nitrates.

- Effective control involves a mix of methods, including mechanical removal, mulching, and appropriate herbicide use, alongside managing seed-bank longevity.

What is Common Lambsquarters (Chenopodium album)?

Common lambsquarters, scientifically known as Chenopodium album, is a plant I encounter quite frequently. It’s a summer annual, meaning it completes its life cycle within a single growing season, and it’s considered a major weed in many agricultural settings, particularly in crops like corn, soybeans, sugar beets, and potatoes. My first real introduction to it was in my own vegetable garden, where it seemed to sprout up everywhere after I turned the soil.

This plant is remarkably adaptable and thrives in a variety of conditions, especially in areas where the soil has been disturbed, like gardens, fields, and even around old farmsteads. The stems can grow to be about 2 to 3 feet tall, and they often have a slightly succulent feel with streaks of red or light green. The leaves are where it gets its common name, sometimes resembling a goose’s foot, and they’re often covered in a powdery, mealy substance, especially on the underside, which gives them a whitish, almost shimmering appearance. It’s interesting to note that it’s related to edible plants like spinach and beets, and it can even share some of the same pests and diseases. I’ve also learned that it can host insects that are problematic for crops, such as the common stalk borer and green peach aphids.

Historically, this plant has a long association with human use. Evidence suggests that people in Bronze Age Asia and Europe were already consuming its leaves. By the 9th century in England, it was a common sight at harvest festivals, often served with lamb and bread made from the season’s first grains, which is how it likely got its name. It’s sometimes called “wild spinach” because of its leafy nature. The seeds themselves can be ground into flour, similar to how quinoa, a close relative, is used. I find it fascinating that a plant often viewed as a nuisance has such a deep history as a food source. Each plant is capable of producing a staggering number of seeds, often over 70,000 in a single season, and these seeds can remain viable in the soil for decades.

Here’s a quick look at some of its characteristics:

- Family:Amaranthaceae (Amaranth family)

- Growth Habit: Summer annual

- Height: Typically 2-3 feet tall

- Leaves: Alternate, variable in shape, often with a powdery coating

- Seed Production: High, with seeds capable of long-term dormancy

It’s important to understand its biology because its persistence is a key factor in why it’s so widespread. The seeds don’t all germinate at once; some might sprout the following year, while others can lie dormant for 10, 20, or even more years, waiting for the right conditions, like soil disturbance, to trigger germination. This makes managing it a long-term effort, much like dealing with field bindweed.

The plant’s ability to produce so many seeds, coupled with its long dormancy and germination triggers, makes common lambsquarters a formidable presence in many environments. Its adaptability means it can thrive in less-than-ideal conditions, further contributing to its widespread distribution.

How to Identify Lambsquarters Seedlings & Mature Plants

Spotting common lambsquarters, whether it’s just a tiny sprout or a full-grown plant, is pretty straightforward once you know what to look for. I’ve found that paying attention to a few key features really helps.

When they’re just starting, lambsquarters seedlings are easy to miss. They often have a pair of oval-shaped leaves, called cotyledons, that are smooth. But the real giveaway comes with the next set of leaves. These true leaves are usually a bit more triangular or diamond-shaped, and they often have a powdery, whitish coating, especially on the underside. This coating gives the leaves a slightly dusty or mealy appearance, which is a signature trait. The stems can also start showing faint reddish streaks.

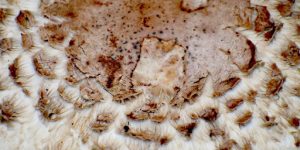

As the plant matures, it becomes more noticeable. Common lambsquarters can grow quite tall, sometimes reaching up to three feet or more. The stems are generally smooth, with those characteristic red or light green stripes running down them. The leaves are arranged alternately along the stem. They vary in shape, but many are somewhat triangular or have a shape that resembles a goose’s foot – hence one of its common names, “white goosefoot.” Like the seedlings, the mature leaves are often covered in that powdery, white, mealy substance, particularly on their undersides. This powdery coating is a really good indicator that you’re looking at lambsquarters, and it’s a feature that helps distinguish it from other plants. You might also notice small, greenish flowers clustered in the leaf axils and at the top of the plant.

Here’s a quick rundown of what to keep an eye out for:

- Leaves: Often coated with a powdery, whitish substance, especially underneath. Leaf shape can vary, but often resembles a goose’s foot or is somewhat triangular.

- Stems: Smooth, with red or light green stripes.

- Growth Habit: Can grow quite tall and bushy, with leaves arranged alternately on the stem.

The powdery coating on the leaves is a really strong clue. It’s like a natural sunscreen for the plant, protecting it from harsh sun. This feature is present from the seedling stage right through to maturity, making it a reliable identification marker for common lambsquarters seed and plants.

If you’re interested in foraging, knowing these identification markers is key to finding edible plants like this one. You can find out more about how to prepare it by identifying and foraging for lamb’s quarters.

It’s worth noting that a single common lambsquarters plant can produce a massive amount of seeds, which is why it’s so widespread. Understanding how to identify the common lambsquarters seed and the plant itself is the first step in managing it in your garden or field.

Seed Biology & Dormancy

It’s quite remarkable how persistent common lambsquarters seeds are in the soil. One of the main reasons this plant is so widespread and difficult to get rid of is its seed’s incredible ability to stay dormant for extended periods. A single lambsquarters plant can churn out a staggering number of seeds, sometimes upwards of 70,000 in just one season. But it’s not just the quantity; it’s the longevity.

These seeds don’t all sprout at once. They have varying levels of dormancy, meaning some might germinate the following year, while others can lie in wait for a decade or even twenty years, especially if they’re buried deeper in the soil. This staggered germination is a survival tactic that ensures the plant’s presence year after year. Seeds tend to germinate best when they’re in the top inch of soil. This is why disturbing the soil, like during tilling or digging, often leads to a fresh outbreak of lambsquarters, bringing those dormant seeds to the surface where light and warmth can trigger their growth. It’s a bit like a hidden seed bank just waiting for the right conditions.

The ability of lambsquarters seeds to remain viable in the soil for many years is a key factor in their persistence. This long-term dormancy allows the plant to survive unfavorable conditions and re-establish itself whenever the soil is disturbed.

Several factors influence seed dormancy and germination:

- Light: Seeds generally require light to germinate, which is why tillage that brings them to the surface is so effective.

- Temperature: Optimal germination occurs within a specific temperature range, typically during warmer periods.

- Moisture: Adequate soil moisture is necessary for the germination process to begin.

Interestingly, much like how American linden seeds require stratification to break dormancy, some research suggests that certain conditions might influence lambsquarters seed viability, though the exact mechanisms are complex. Managing this persistent seed bank is a major part of controlling lambsquarters in the long run. Understanding how these seeds survive and germinate is the first step in developing effective strategies to keep them in check. For instance, knowing that seeds need light to sprout helps inform practices like minimizing soil disturbance where possible. If you’re dealing with a persistent weed problem, understanding the biology of the seeds is quite helpful.Managing this seed bank is key.

Edible Uses & Nutritional Value of Lambsquarters Seeds and Greens

It might surprise you to learn that this common weed, often seen as a nuisance in gardens, has a history of being used as food. I’ve found that lambsquarters, or Chenopodium album, is actually quite nutritious. People have been eating it for centuries, even back to Bronze Age times. It’s sometimes called ‘wild spinach’ for a good reason.

Both the young leaves and the tender stems can be eaten. I usually prefer to cook them, much like spinach or other greens. They can be boiled or sautéed. The leaves have a mild flavor, and when they’re young and tender, they’re really quite pleasant. The plant is a good source of iron and vitamin C, and it also contains other minerals.

Here’s a quick look at what I’ve gathered about its nutritional content compared to cultivated spinach:

| Nutrient | Lambsquarters (per 100g raw) | Spinach (per 100g raw) |

| Calories |

43 |

23 |

| Protein (g) |

2.7 |

2.9 |

| Iron (mg) |

3.2 |

2.7 |

| Vitamin C (mg) |

49 |

28 |

| Vitamin A (IU) |

4,786 |

5,047 |

Beyond the greens, the seeds are also edible. They are tiny, but they can be dried and ground into a flour. I’ve read that this flour can be used to make bread, cakes, or a simple gruel. It’s interesting to note that quinoa, a popular grain, belongs to the same genus as lambsquarters.

I’ve tried making a simple salad with the young, raw leaves, and it was surprisingly good. The texture is a bit different from store-bought spinach, a little more robust, but the taste is mild and earthy. It’s a good reminder that sometimes the best ingredients are right under our noses, even if they’re considered weeds.

Historically, the plant has also been noted for having medicinal properties, though I focus on its culinary uses. It’s a plant that really has a lot to offer if you look past its weedy reputation.

Risks & Toxicity

While common lambsquarters is often discussed for its edible qualities, it’s important for me to acknowledge the potential risks associated with it, especially concerning livestock. This plant does contain compounds that can be problematic if consumed in large quantities.

One of the main concerns is the presence of oxalic acid. This compound is particularly noted for its potential to cause issues in sheep and swine. If these animals ingest significant amounts of lambsquarters, it can lead to poisoning. The oxalic acid can bind with calcium in the animal’s system, potentially causing problems.

Nitrates are another factor to consider. Lambsquarters can accumulate nitrates from the soil, and high nitrate levels in forage can be toxic to livestock, including cattle. The risk often depends on soil conditions and the plant’s growth stage.

Here’s a quick rundown of what I’ve observed regarding toxicity:

- Oxalic Acid: Primarily a concern for sheep and swine. Large ingestions can be toxic.

- Nitrates: Can accumulate in the plant, posing a risk to cattle and other ruminants if levels are high.

- General Caution: As with many plants, moderation is key. Feeding large amounts of lambsquarters, even if otherwise healthy, can lead to digestive upset.

It’s also worth noting that lambsquarters can sometimes harbor pests and diseases that affect crops like beets and spinach, which might be a secondary concern if you’re considering it for fodder. For those interested in using plants like lambsquarters to improve soil health, practices like green manuring can be beneficial, but it’s always wise to be aware of the plant’s composition. Green manuring enhances soil properties.

When considering lambsquarters for any purpose, especially related to animal feed, it’s best to err on the side of caution. Understanding the potential for these compounds to accumulate and cause harm is part of responsible land and animal management. I always recommend consulting with local agricultural extension services or a veterinarian if you have specific concerns about feeding this plant to your livestock.

Impact on Crops

When common lambsquarters shows up in a field, it’s not just a nuisance; it can really mess with your crop yields. This weed is a tough competitor, especially when it gets an early start. It’s known to grow fast and can quickly outcompete young crops for vital resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients.

I’ve seen firsthand how dense stands of lambsquarters can significantly reduce the harvest. Studies and field observations suggest that even moderate populations can lead to noticeable yield losses. For instance, densities of over 200 plants per square yard have been reported to cut barley yields by as much as 20-25%. Given that wheat is generally less competitive than barley, you can expect even greater reductions in wheat fields under similar conditions.

Here’s a breakdown of why it’s such a problem:

- Resource Competition: Lambsquarters actively competes with crops for water, nutrients (it’s particularly good at taking up phosphate early on), and sunlight, stunting crop growth.

- Allelopathy: Some research suggests that lambsquarters might release compounds into the soil that can inhibit the growth of nearby crop plants, though this is less commonly discussed than direct competition.

- Harvest Contamination: The seeds of lambsquarters can contaminate harvested grain or grass seed, reducing their quality and marketability. The green matter can also be an issue in cereal seed.

- Pest and Disease Hosting: It can act as a host for certain insects and diseases that also affect crops like corn, tomatoes, and sugar beets, potentially increasing pest pressure in your fields.

The sheer number of seeds a single lambsquarters plant can produce, coupled with their long-term viability in the soil, means that even a small infestation can quickly escalate into a major problem if not managed properly. This persistence is a key factor in its widespread impact on crop production.

Managing lambsquarters early is really the best approach. Waiting too long means the weed has already done much of its damage by stealing resources and potentially impacting the crop’s ability to thrive.

Integrated Control Strategies

When it comes to tackling common lambsquarters, I’ve found that a mix of approaches usually works best. It’s not just about one thing; it’s about putting several tactics together.

For small patches or in a home garden setting, mechanical methods are my go-to. A good old-fashioned hoe can do wonders, especially when the plants are young. Just a quick chop at the base, and they’re usually done for. Cultivation, like tilling or using a cultivator, also works well to uproot them before they get too big or start setting seed. If I’m dealing with a larger area, I might consider mulching. Things like black plastic or even a thick layer of straw over newspaper can really suppress them, keeping sunlight away from any seeds trying to sprout.

When it comes to herbicides, I’m always careful. It’s important to read and follow the label directions precisely. Different herbicides work on different crops, and what’s safe for one might not be for another. I’ve seen that some common lambsquarters have developed resistance to certain types of herbicides, like those in the triazine and ALS-inhibitor families. This means I might need to switch things up or use a product with a different active ingredient, such as dicamba, which often works well, especially on younger plants. It’s a good idea to check with local resources, like your county extension office, for the most current recommendations for your area. They can provide advice on managing herbicide resistance, which is a growing concern for many farmers across the U.S., and combating herbicide-resistant weeds.

Here’s a breakdown of what I consider:

- Mechanical Control: Hoeing, hand-pulling, and cultivation are effective, particularly when plants are small and before they produce seeds.

- Cultural Control: Practices like mulching, crop rotation, and maintaining healthy, competitive crops can help reduce lambsquarters populations.

- Chemical Control: Herbicides can be used, but it’s vital to select the right product for the crop and to be aware of potential herbicide resistance in lambsquarters populations.

Managing lambsquarters effectively often means combining these methods. Relying on just one strategy might not be enough, especially if the weed pressure is high or if resistance is a factor. Thinking about how the seeds persist in the soil is also key to long-term control.

I also pay attention to the timing. Trying to get rid of lambsquarters before they go to seed is the most important thing I can do. If they manage to produce seeds, those seeds can stay viable in the soil for a long time, meaning I’ll be dealing with them again next year and the year after that.

Best Practices for Seed-Bank Management & Prevention of Lambsquarters Recurrence

Dealing with common lambsquarters long-term means thinking about its seeds. These little guys are tough and can hang out in the soil for years, just waiting for the right moment to sprout. So, my approach has to be about managing that seed bank.

First off, I try to stop plants from going to seed in the first place. If I see them in my garden or fields, I pull them out before they get a chance to make more seeds. It’s a bit of a numbers game, and every plant I remove before it seeds is thousands of potential plants I won’t have to deal with later.

When it comes to tilling, I’ve learned to be more mindful. While tilling can bring weed seeds to the surface, which can be good if I’m going to cultivate or use a pre-emergent herbicide, it can also bury seeds deeper. Seeds buried deeper might not get the light they need to sprout right away, but they can survive for a really long time. So, I’m trying to use less aggressive tillage or no-till methods where possible, especially in areas where I’ve had a lot of lambsquarters.

Here’s a quick rundown of what I focus on:

- Prevent seed set: This is the absolute priority. Remove plants before they flower and produce seeds.

- Minimize soil disturbance: Tilling can bring dormant seeds to the surface. Consider reduced tillage or no-till where practical.

- Crop rotation: Rotating crops can help break the life cycle of lambsquarters and reduce the buildup of seeds in the soil.

- Cover cropping: Planting cover crops can outcompete lambsquarters and suppress germination.

- Timely cultivation/hoeing: Get them when they’re small and haven’t established deep roots or produced seeds.

I’ve also noticed that lambsquarters seems to like certain conditions. It pops up a lot in areas with high organic matter, which makes sense given its history as a forage. So, managing soil fertility and organic matter, while important for my crops, also needs to be done with an eye on weed pressure.

The key to managing lambsquarters over time is a consistent, multi-pronged strategy. It’s not about a single fix, but about layering different methods to gradually reduce the seed population in the soil and prevent new seeds from being added. This takes patience and observation, but it’s the only way I’ve found to really get ahead of it.

Keeping your seed bank healthy and preventing weeds like lambsquarters from coming back is super important. We’ve put together some easy-to-follow tips to help you manage your seed bank effectively. Want to learn more about keeping your fields weed-free? Visit our website for detailed guides and solutions!

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is common lambsquarters?

Common lambsquarters is a plant that often grows where the soil has been disturbed, like in gardens or fields. It’s considered a weed because it can grow very quickly and take over. Interestingly, it’s related to spinach and beets and has been eaten by people for a very long time, even being part of an old English harvest festival meal.

How can I tell if I have lambsquarters in my garden?

Young lambsquarters plants have smooth leaves that might look a bit dusty or white, especially underneath. As they get bigger, the leaves are often shaped like a goose’s foot and have jagged edges. The stems can sometimes have red or green stripes and feel a bit watery.

Why does lambsquarters keep coming back year after year?

This plant is a champion at making seeds – one plant can produce over 70,000 seeds! What’s more, these seeds don’t all sprout at once. Some might pop up the next year, but others can stay asleep in the soil for 10, 20, or even more years. They usually need light and warmth near the soil surface to start growing, which is why tilling the soil often brings them up.

Can I eat lambsquarters?

Yes, you can! Both the young leaves and stems are edible and can be eaten raw or cooked. Many people find they have more protein, vitamins, and minerals, like iron, than spinach. The seeds can even be ground into flour for baking. It’s sometimes called ‘wild spinach’ for good reason.

Are there any dangers associated with lambsquarters?

While it’s edible, it’s important to be cautious. Lambsquarters contains natural substances called oxalates and can also take up nitrates from the soil. If animals like sheep or pigs eat large amounts, this can cause poisoning. For humans, eating very large quantities might also be a concern, so moderation is key.

How do I get rid of lambsquarters if it’s taking over my garden?

For small patches, pulling them out by hand or using a hoe works well, especially when they are young. Keeping the soil covered with mulch, like straw or black plastic, can also stop the seeds from growing. In larger areas like farms, special weed killers (herbicides) can be used, but it’s important to know that some types of lambsquarters have become resistant to certain common weed killers.